EP. 11: ON READING THE BODY

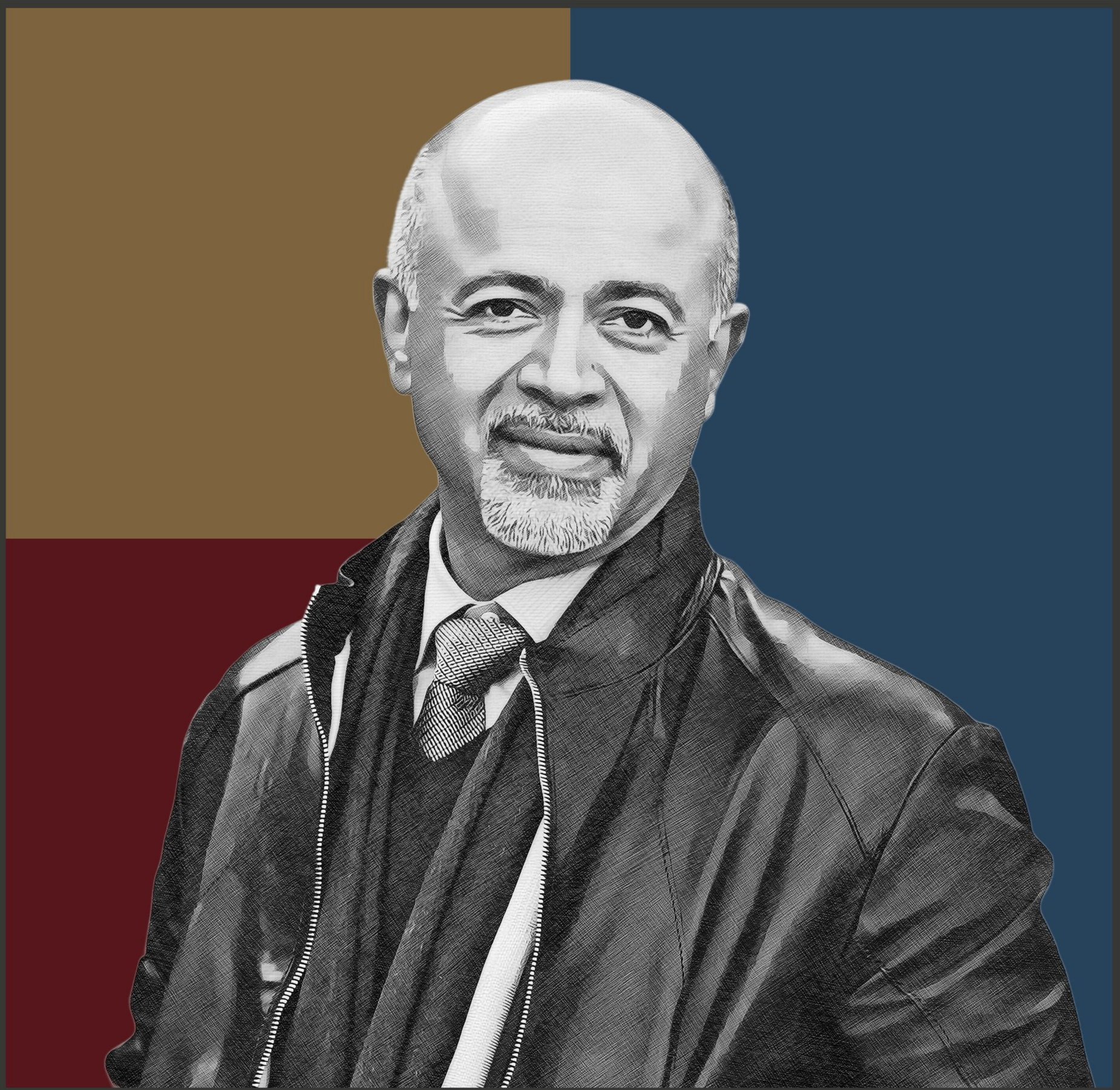

WITH ABRAHAM VERGHESE, MD

A physician and bestselling author discusses why the human touch still matters for healing in our increasingly digital age.

Listen Now

Episode Summary

Dr. Abraham Verghese is a prolific writer and revered physician who has deeply contemplated the philosophical underpinnings of the practice of medicine. He is renowned as an advocate for the importance of bedside examination and physical diagnosis, and his best-selling books probe the intricacies of human connection in the context of healthcare. In this episode, Dr. Verghese discusses how maintaining a literary life has impacted his approach to doctoring, why the human touch still matters for healing in our increasingly digital age, and his vision of the future of medicine.

-

Dr. Abraham Verghese is a physician, humanists, and author whose three books Cutting For Stone, My Own Country, and The Tennis Partner have all been national or international bestsellers. He has published extensively in the medical literature and has written essays for The New Yorker, The Atlanic, The Wall Street Journal, and the other notable publications across the United States.

Dr. Verghese is currently Professor and Senior Associate Chair for the Theory and Practice of Medicine in the Department of Medicine at Stanford University. As a leading advocate for the value of bedside skills and physical diagnosis, he leads an initiative at Stanford teaching fundamental physical exam and diagnostic skills to residents. In 2016, he was awarded the National Humanities Medal by President Barack Obama.

-

How a college music reviewer came to write for The New York Times - 1:41

• How Dr. Verghese’s love of literature influenced his decision to enter medicine - 2:39

• Reflections on the challenges of contemporary medicine - 7:51

• How physical exams can be seen as a ritual for “reading the body like a book” - 10:07

• Dr. Verghese’s perspective on the future of doctor-patient relationships given the rise of telemedicine and other technologies - 20:36

• Balancing the need to connect with each patient for their treatment, while being responsible for so many at once - 26:23

• How the craft of writing relates to medicine for Dr. Verghese - 31:50

• The counterintuitive diagnostic efficiency of taking the time and care to meet patients where they are at - 35:45

-

Henry Bair: [00:00:01] Hi. I'm Henry Bair.

Tyler Johnson: [00:00:03] And I'm Tyler Johnson.

Henry Bair: [00:00:04] And you're listening to The Doctor's Art, a podcast that explores meaning in medicine. Throughout our medical training and career, we have pondered what makes medicine meaningful. Can a stronger understanding of this meaning create better doctors? How can we build health care institutions that nurture the doctor patient connection? What can we learn about the human condition from accompanying our patients in times of suffering?

Tyler Johnson: [00:00:27] In seeking answers to these questions, we meet with deep thinkers working across health care, from doctors and nurses to patients and health care executives. Those who have collected a career's worth of hard earned wisdom, probing the moral heart that beats at the core of medicine. We will hear stories that are, by turns heartbreaking, amusing, inspiring, challenging and enlightening. We welcome anyone curious about why doctors do what they do. Join us as we think out loud about what illness and healing can teach us about some of life's biggest questions.

Henry Bair: [00:01:03] We are honored to be joined today by Dr. Abraham Verghese, who is arguably one of the most celebrated physician writers and humanists in practice today. His three books Cutting for Stone, My Own Country, and The Tennis Partner, have all been national or international bestsellers and have garnered numerous accolades. In addition, he has published extensively in the medical literature and has written essays for The New Yorker, The Atlantic, The Wall Street Journal, and other notable publications across the United States. Dr. Verghese is currently professor and Senior Associate Chair for the Theory and Practice of Medicine at Stanford University. As a leading advocate for the value of bedside skills and physical diagnosis, he leads an initiative at Stanford teaching fundamental physical exam and diagnostic skills to residents. In 2016, he was awarded the National Humanities Medal by President Barack Obama.

Tyler Johnson: [00:01:54] On a more personal note. I met Dr. Verghese a number of years ago when I was an intern on his internal medicine service at Stanford Hospital and have looked to him since then as a mentor and example and someone who I really admire. And so we are really grateful to have you here and we're glad that you would lend us some of your time today, Dr. Verghese. Thanks so much for being here.

Dr. Abraham Verghese: [00:02:16] Thank you so much, Tyler. It's a pleasure to be with you. And as you said, I've delighted in watching you go from being intern to resident to my chief resident. And now to join us on the faculty as an oncologist. So, truly a privilege to watch you. I think that summarizes all that's beautiful about being a teacher of medicine.

Tyler Johnson: [00:02:39] Well, thank you. That means a lot. So actually, speaking of the process of becoming a doctor, we would love if you could share with us, and I know you've written about this extensively, but nonetheless, for our listeners, if you could share with us a little bit about your origin story. How did you end up becoming a doctor? Why did you go into medicine?

Dr. Abraham Verghese: [00:02:58] Well, my parents are we are Indian origin. My parents were from India, but they were working in Ethiopia as schoolteachers. And my brother and I, my older brother and I were born there. My younger brother came later. Middle class Indian families are, "You can be a doctor or a lawyer or a failure. These are your options." All right? Good engineer, I suppose. But I didn't really have any particular calling for medicine. I knew that I wasn't going to be an engineer. I didn't really have that kind of interest. Paradoxically, it was a book that brought me to medicine, which is true. I think of that era for a lot of us, it wasn't so much a TV show or anything else, but it was books and it was of Human Bondage by Somerset Maugham.

Dr. Abraham Verghese: [00:03:45] The story there is actually very little to do with medicine. The protagonist is a young boy born with a clubfoot, orphaned very early on, brought up by foster parents. He has a very miserable childhood. And his only escape is art. And he, much over the objections of his foster parents, he comes of age and goes to Paris to be an artist. And when he first gets there it's a magnificent life. He's doing his art and, you know, living the life. But then reality begins to sink in. And one day, he's standing outside his apartment. He sees his art teacher walking by, a gentleman by the name of Monsieur Feeneyy. And on an impulsive he stops him and says, "Would you please come up and take a look at my paintings? Because I'm really debating whether to go on." Against his better judgment that the teacher decides to do that and goes up with him and looks at all the paintings and then finally says something like, "Is there something else you could be doing?" And, you know, it is crushing for Philip, the protagonist, to hear that. But on the other hand, it's exactly what he wanted to hear. He really wanted to know whether to go on with this. And Mr. Feeney goes on to say an interesting thing. He says, "Don't take this badly. I wish someone had told me what I'm telling you when I was your age. There's nothing worse for the temper than discovering one's own mediocrity at an advanced stage." That's the exact line. And so Philip goes back to London where there's a small annuity for him if he pursues a professional education. So he goes into medicine and the first couple of years are drudgery. And finally he arrives in the wards and sees patients and Somerset Maugham's lines are, "Philip saw humanity there in the rough. The artist's canvas. And he said to himself, "This is something I can do, something I could possibly be good at."

Dr. Abraham Verghese: [00:05:48] And you know, those words really rang true for me because I was a very undistinguished scholar. My older brother was and still is just a brilliant mathematician, a professor at MIT now. And he clearly had all the makings to be an engineer, which was what he wanted to be. And I was lost. I had no idea what I wanted other than I like to read. But those words really implied to me that not everybody could be a great artist or be a great mathematician. But anybody... I think this is key for your listeners... Anybody who has a basic curiosity about the human condition with a basic empathy for their fellow human beings could become a very good physician. That's what I took away. And so that was really the moment that I had my calling to medicine. And interestingly, I think this is what books do for you. You know, books interrogate you and they give you a wisdom that you wouldn't have from just living your life. And, you know, some epiphany was quiet. I didn't really make any grand pronouncements. They just knew in my head from reading that book, and I didn't think anybody would understand why, that I wanted to be a doctor.

Tyler Johnson: [00:07:04] You know, we've talked a lot with many of our guests on the podcast about how we hear from individual practitioners that they feel like they've lost their connection to what makes medicine most meaningful. But it also feels... I think there's a broader sense... There's sort of a spirit moving on the waters in a way, in the field of medicine in general, that it feels like maybe the field is adrift and even the broader medical consciousness doesn't really remember what we're doing here sometimes. And I'm wondering, if you were to speak to that, what do you feel is the deeper meaning for medicine? And how can both we as individuals and we as a medical field become more in touch with that?

Dr. Abraham Verghese: [00:07:47] You know, these are very challenging times. I mean, I think we live in an incredible age of medical discovery and technology and therapeutics. I mean, your field, for example, the kinds of things that we can now cure, or at least prolong life, were unimaginable when I was in training or even just ten, twenty years ago. They were just not realistic. But it has that kind of advances come at a price in the sense that it is complicated. It requires teamwork. It requires very complex systems. It requires all kinds of things that increasingly make it harder to have that personal connection when it was just you and the patient and everything revolved around that dyad. And now, now it's much more about teams. And that's not necessarily a bad thing. But I think it can rob you of the sort of immediate feedback and get you so bogged down in all the day to day charting and this and that, that you you can lose touch. And I think we have more than ever, we have to really work at reconnecting with what brought us to medicine. Touching the cloth again and finding the faith. We have to do that regularly because if you don't you will really get quite discouraged. And I think it's been interesting to watch the last few years because, you know, a lot of people have become quite discouraged. And part of it, I think, is we need to keep our focus on the prize. And the prize is human health, It's prevention. It's society living longer. We're managing all that along with great political strife and great climate challenges and so on. So these are stressful times, but I think it remains important to me to acknowledge the great privilege of being allowed into people's lives at their most intimate and scary moments, and to be some sort of a guide and comfort to them. It may not be happening as much one on one as you as you would want, but I think for that reason, every interaction is even more loaded than it used to be because there are so few opportunities for you to make that difference.

Henry Bair: [00:10:07] Dr. Verghese, one of your most notable teachings is about the transformative potential of the human touch and of the physical exam. In one of your TEDTalks, you describe one of the most powerful tools a clinician has at his or her disposal as the human hand. So I was wondering what first clued you in to the power of the human touch, and how did you come to develop this philosophy of medical practice? If it is apt to describe it as such.

Dr. Abraham Verghese: [00:10:38] Yeah. Thank you, Henry, for that question. It's very clear that one can read the body like a book. And the great joy for me in entering medicine and especially entering my field of internal medicine was the recognition that I was now being gifted with this ability or literacy that the layperson did not have. You know, I could look at a body and discern things about the physiology about them, you know, sort of Sherlock Holmes kind of way that I thought was fascinating. And to this day, I'm in great danger at airports because I get bogged down just looking at people walking down those long, long corridors or, you know, just the humanity on display. You know, it's all I can do to not tap people on the shoulder and ask them questions to sort things out. So I've always loved that skill and the fact that we can now confirm and affirm this in so many different ways. The things that our exam tells us, you know, through ultrasound, X-ray, CAT scan, you would think would make us 100 times better than, say, physicians of Sherlock Holmes era, that that vintage. But instead, you know, we've become 100 times worse. It's really quite sad to see how poorly we do as physicians, recognizing what's right in front of us and often with great consequences. You know, we make diagnostic errors, we delay therapy, we expose people to needless radiation and surgical and therapeutic misadventures, all because we just didn't recognize what our predecessors of 100 years ago would have gotten right away.

Dr. Abraham Verghese: [00:12:24] There's a very basic reason to do the physical exam because I think it's a basic step. But more than that, I think, especially from my experience with patients with chronic fatigue, I came to realize that there was something more to this. You know, I... I had the experience, especially in Texas, where I had this reputation of being interested in patients with chronic fatigue, which wasn't necessarily true. I'm not sure how it came about, but I realized that these patients were very difficult. They had volumes to tell you. And if you tried to do it all in a 40 minute new patient encounter, I mean, I couldn't do it. So I gave them a visit entirely to hear their story, which, as it turns out, is also crucial. People have a need to tell you what they're experiencing. Even if you know what's going on from the outset, they have a need to tell it their way. And I would schedule the physical for another time. And so when they came, you know, that's all we had to do was do the physical. And to my dismay, my first or second patient in this series continued to tell me more, more history on the second visit, even though we had very clearly made this distinction between history and physical.And I just decided to launch into my exam. And, you know, we all have our way of beginning the physical exam. And I think it's most natural to begin with a shake hands gesture because it's socially acceptable. And and so I shake hands, but I'm registering so many things about the hand, you know, the warmth, the sweatiness, the duplications. And we could spend one hour literally talking about the hand. And my right hand is thus engaged, but my left hand comes around and I'm feeling the pulse and I'm feeling the rate, the rhythm, the volume, the character of the vessel wall. And then my left hand slips up to the cochlear lymph node at the elbow. And now I am just in my ritual, you know, it's sort of like a cascade of things I do. And because I've been doing it for almost 40 years now, for 40 years, it just... It can... It's automatic. It's got a smoothness to it. It's probably not as detailed as what we teach our students, but I can expand it anytime I need to.

Dr. Abraham Verghese: [00:14:42] And a very interesting thing happened. This very voluble patient quieted down and stopped talking. And I had an eerie sense that the patient and I had slipped back into a primitive ritual, a dance of sorts, in which I had a role. They had a role. And when I was done, the patient said to me with some, "Oh, I have never been examined like this before." And if that were true, I thought it was a real condemnation of our health care system because they'd been seen by many people before, and all I did was a routine exam. And I always thought that somehow the exam was the reason that this patient gave up the quest for the magic doctor, the magic injection, and instead began a partnership with me towards wellness.

Dr. Abraham Verghese: [00:15:31] And I confess I didn't quite understand this till I came to Stanford. And the great joy of being here, as you know, is this is the first medical school in six or seven that I... That I've now spent my career at. Where the... The other schools are on the same campus, School of Law, Engineering, Humanities, Arts and Sciences. And so you can just walk across the parking lot. They're not across the street. They're not across the freeway. They're right there.

Dr. Abraham Verghese: [00:15:59] And so I talked to my anthropology colleagues about this... This experience, and they immediately pointed out to me that I was describing a ritual, that this had all the trappings of ritual. And they taught me that rituals are all about transformation. We signal the crossing of a threshold by rituals such as weddings and bar mitzvahs and baptisms. And if you look at this, you have a stranger coming to see you. And when they come to see my trainees, they're coming to see people who are half their age or one third their age, telling them things they would never tell their rabbi or their preacher. In my specialty, infectious disease, telling me things they would never tell their spouse. And all of this is in a room whose furniture doesn't look like the furniture in your house or mine. One individual in this dyad is wearing a white shamanistic outfit with strange tools in the pocket, and the other is wearing a paper gown that no one knows how to tie or untie. It's part of the great mystery of this ritual. And then, incredibly, one individual disrobing and allows touch, which in any other context in our society is assault, but the great privilege of being a physician. And it comes with the fiduciary responsibilities that we are allowed this touch in order to read the body. And let me tell you, I think that physicians don't seem to understand that patients are excellent judges of how well you're doing that stuff. If after all that rigmarole, you just do a half assed prod of the belly and stick your stethoscope on the gown, which to me is heresy, then they are onto you, just as you and I are on to the sloppy barista. The sloppy mechanic. The sloppy short order cook. The sloppy hairdresser. We may not know how to do what they do, but we all recognize when someone is doing something.

Dr. Abraham Verghese: [00:18:05] Well. In fact, one of our Stanford students long ago pioneered something where he had laypeople watch surgeons performing surgery. You know, they don't know. Knew nothing about the surgery, but it turned out they were excellent at rating surgeons based on observing them. And so I think there's an important buy in when you do the physical, quite apart from all the data that you discern, that allows you to order tests more judiciously, order tests that others wouldn't think to order because they hadn't picked this up. You know, so I've become a fan of that and I've become concerned that without this being passed on, and you can't learn this on the Web, you can't learn this any other way. As Tyler knows, other than by being an acolyte and someone leading your hand to feel what they feel and hear what they hear and see what they see. It's a... It's a tedious method of learning, but that's how I learned, and that's the only way to convey it. And if we don't commit ourselves to to teaching it, it will quickly die. It is probably already died in many places.

Dr. Abraham Verghese: [00:19:12] And so you have this phenomenon of patients feeling like they're being just run through machines and then the results are spat out and then they're told to do this and that. And you don't blame them for having absolutely no faith in the recommendations being made because they they don't feel, I mean, I talked about rituals, having a transformation. You know, every ritual has a transformation. It's a crossing of a threshold. The transformation of this ritual, when done well, is that you're localizing the patient's complaints on their body, not on a biopsy result, not on an x ray, not on a CAT scan. But you're embodying the patient's identity and you're localizing this distress on their body. You're recognizing and acknowledging it. And it turns out, I think it's terribly important, you know, as Tyler knows, that we often round at Stanford and you're seeing a patient who 20 to 30 different people have already seen. You know, different specialties, consultants. And very often that seeing simply consists of them appearing at the bedside and disappearing. And, you know, I try to make it a point to to examine them not... Not in a great, detailed way, but at least to do something. It turns out often they remember that. I always feel that it buys me a certain level of connection that I wouldn't have had otherwise.

Tyler Johnson: [00:20:36] Dr. Verghese, having known you for many years, it's become ingrained in me to think of doctors as having... I don't know if it's exactly dual purposes, but let's say there are two different approaches maybe is a better way of saying it, where on the one hand the doctor has a sort of a functional role to play, right? Which is to answer a series of questions and figure out which tests need to be ordered and assign a diagnosis and a treatment plan, which you can imagine in some future that an artificial intelligence entity could probably do most of those things as well or better than humans do. Right? But then there is this whole other aspect to medicine that seems to be best described by words like spiritual or almost something bordering on religious, Right? Which is, you invoke words like ritual and ceremony and transformation and all of those things which have spiritual connotations to them. One thing that I have been really struck by is that for multiple reasons, during the pandemic, it seems like there was an almost immediate shift to doctor as functionary, right? Part of this is because doctors and nurses and all health care workers were just so beaten down by the difficulty, the difficulties that everybody experienced in the pandemic. And then on top of those, the fact that they had to show up and be heroes at work every day. And it was just exhausting. But then, the other part of it is that in many ways that I don't think anyone could have foreseen five years ago, there was this dramatic shift in the way that medicine is practiced. So that, for example, I haven't seen figures on this, but a very high percentage of visits are done by video, where many of the most important aspects of the physical exam aren't even possible. Right? I mean, certainly you can't touch the patient. You can probably see some things and maybe you could hear a few of them. But it's but the interaction is then stripped of many of its most intuitively spiritual aspects. And I guess what has been somewhat surprising to me, at least in my own practice and those of people that I've observed around me, is that I figured this would be sort of an elastic band that we had sort of stretched tight. And then as the pandemic waned, we would let go and it would snap back to where it was before. But it's not obvious to me that that's happening. At least I know a lot of my patients still like video visits because of the increased convenience and everything else. And so I guess partly this is an observation, but partly I guess I'm asking as somebody who has been standing in the wilderness proclaiming the importance of all of this even before the pandemic happened, how do you see the way forward as a field? How do we try to not lose sight of, or to the point, touch with those important other aspects of what it means to be a doctor?

Dr. Abraham Verghese: [00:23:21] Yeah. I think you're going to be surprised, Tyler, by what I have to say about telemedicine, because I must confess, I was quite humbled by it. I was prepared to disapprove of it for all the reasons you mentioned. But, you know, having witnessed it, watched my colleagues do it, done it myself, being a patient and had a telemedicine encounter, it just seemed to me that I had really not quite fully understood its potential. So if you're bringing in an older person and making them get up early, shower or get in their car, find parking, come to order for you to do this half assed part of their belly or no... No prod at all. Just sit them there and pontificate. Then why bother to bring them in? You know, it certainly could be done by phone. I would actually say the challenge is to prove to many of our colleagues that coming in has actually done anything different than what they do. Because in many ways, if you don't examine the patient, really, you know, how much do you really need to do that? You couldn't do this way. But more than that, I think what was most humbling to me was to look at the patients backdrop and getting a sense of who this person is. And, you know, I'm embarrassed to say that for all our lip service about social determinants of health and this and that, I don't think I ever understood who patients really were until I started to see them in this context and see the number of family members crowded into that one room or a beloved pet who clearly was huge in their lives, or to recognize that they were calling from a outside a Holiday Inn because they had no wi fi, and that was the best they could do, you know.

Dr. Abraham Verghese: [00:25:10] So I think there's been an opportunity to peek into people's personal lives and really connect with them better. I'm not sure that we can do this exclusively. I think there should be some amalgam and I think already payment for telemedicine has gone back down. So that alone is going to drive people back to coming to the clinics more. But I think the onus is on us to make those clinical visits meaningful. It has to be worthwhile for them to make that schlep there. And Kaiser was way ahead of us on this years ago. They already were putting this as a part of their practice for post-op visits, for hip surgery and this and that. And, you know, literally going to the home before the surgery, equipping it and having their therapists come out there after the surgery, doing tele visits. We were not quite that prepared at Stanford, far from it, and it just took off. And so I don't think it's entirely a bad thing. As you point out, it has its challenges, but the burden is on us to prove that the the converse... That they're coming to clinic is really a higher yield procedure. And if it's not, you can't blame the patients for... For wanting to stay at home.

Henry Bair: [00:26:23] Earlier, I mentioned your approach to patient care as a philosophy, and that's because that's what it felt like whenever it came up. During my time rotating through the wards here at Stanford Hospital, a resident or an attending would often, when rounding on patients, invoke your teachings as of the School of Doctor Verghese, meaning taking the time and the care to not just examine but feel and hold the patient the way that you advocate. At the same time, and I recognize this may be a challenging question, I also see the difficulty of exercising this approach when there's often so much going on. When you have 20 patients on your unit, when you have all the administrative tasks to complete, when you have to manage very difficult and complicated patients, there just doesn't seem to be enough time to care for all patients in the manner that we would like. And so while I think most clinicians intuitively see the value of your approach and wished they could tend to all patients that way, in practice, we don't see it as much as we think we ought to. So my question is how should we strike the right balance? How do we ensure the human connection isn't lost, even in times when we have to manage seemingly too many patients?

Dr. Abraham Verghese: [00:27:49] Yeah. Well, I must say, I'm dismayed if this is being characterized as my... My school, because I'm only doing what we're supposed to be doing and what we're billing for. And in a way, this is sort of the big problem with medicine. We are building and claiming to do things that we're not doing. You just have to look at our... Our computerized medical records. I'm a great fan of fiction. I read fiction. I even write fiction. But I don't think it has a place in the medical record. And yet we're very willing to check dropdown boxes and claimed we've done things that we've not done. You know, it's actually an injurious, moral thing that we're all being subjected to, which is to make claims that are not entirely true. But let's put that aside, because I think that that's a different issue. Again, I'm not unrealistic when you have 12 admissions, you know, there is no time to spend an hour with every person before lunch time. However, you will actually waste a lot more time if you don't go and see the patient and don't get a sense for them.

Dr. Abraham Verghese: [00:28:50] Whenever I take over a new ward service, I find it bewildering to look at the computer for 2 hours and try and read about all these patients, which you need to do. But it only makes sense to me when I go and take a quick look at them. Not... Not a detailed exam, but literally just a visit to eyeball them. Maybe, maybe examine the part that I'm interested in. And only then does all this sort of sift out for me. If you if you think that that's a waste of time there... There's no greater waste of time than ordering a test that you don't need, getting a result that leads you to order something that the patient didn't need. And on and on. I mean, we see this all the time where someone gets a culture that begets a result that and then you start playing antibiotic roulette. And the fundamental premise that they had an infection or needed this antibiotic is wrong. So I would push back. I would say that I'm not advocating people do anything different than what what they should be doing. I don't think it's right to sit in a room and flip cards with residents and students and think that you have therefore rounded on the patient. I don't think it's right in a teaching hospital for you then to go on your own and see the patients. Without the resins and the students, admittedly, you can't do it all the time. You can't do it except maybe on the new patients. But I think that if we're presuming to be a teaching hospital and pass on wisdom and embody and demonstrate and model ways to be, then this is an important step and you have to do it.

Dr. Abraham Verghese: [00:30:23] So if you don't do it, you get burnt. Do we see this all the time where we published a paper on oversights in the physical exam that led to consequences? These are not things that anybody but physicians know about. So we collected stories from physicians about things that had been overlooked in the physical exam that had consequences. You know, everything from people coming in to chest pain, going to the cath lab, contrast, being ingested, injected before someone realizes they have a rash that looks like dewdrops on rose petals and they have shingles or, you know, someone coming in with abdominal pain being labeled gastroenteritis. And the radiologist calls you the next day to say there's gas in the scrotum. The patient has Fournier's gangrene of the scrotum. How could three ships miss that? Well, it can happen. It happens all the time. It's happening all across America because we're very good at process. The computer medical record for the emergency room, the night shift, the day shift, everybody looks great. But somehow people have not picked up the smell in the room from a necrotic scrotum. So this sort of thing happens. And I think, you know, I don't. So I'd like to push back. I don't want... I don't want this to be my little perth eccentricity that we should go see the patient, you know, beware in a long career if you don't see the patient, bad things happen.

Tyler Johnson: [00:31:50] Of course, one of the things that you're most known for is your writing. And I'm wondering if you can talk a little bit about as a doctor, why do you write and how do you decide the things that you will address in your writing? Where does your writing spring from?

Dr. Abraham Verghese: [00:32:09] My writing sort of came much, much later in my career but my first love is... Is medicine very much still remains that to me. The writing is just part of medicine. It's just describing a lot of what I see. And I always resist this notion that I'm a doctor and a writer, you know, even though I know... I know that now that that's that's a bit disingenuous because I clearly am a writer. But I think that I've always been impressed by the fact that many physicians, many medical students, don't recognize that being familiar with the works of great fiction and literature inform you in such incredible ways. And there is no life experience that can give you that in quite the same way. Transport you, teach you about the human condition. If fiction... If fiction resonates for us, it's because there's an element of truth in that. Dorothy Ellison famously said that fiction is the great lie that tells the truth about how the world lives. You can't practice medicine just by knowing the right treatment for this cancer and applying it, because the great variable is the human being that you're dealing with and how they're going to respond to it. And if you want some schooling in that, there's no better way than immersing yourself in literature. And I think we give a lot of lip service to literature. We approach it in college with a certain, you know, I got to do this kind of thing, not recognizing that the way books interrogate us, the way books reveal human nature to us is so incredibly precious. We should be fighting with anybody who keeps us from acquiring that kind of knowledge.

Dr. Abraham Verghese: [00:33:54] In terms of writing, I think it came about from wanting to put words to some of the incredible experiences that I've had. You know, I began writing because I was trying to describe my fraught time in the early HIV epidemic, caring for men who were my age. Primarily, men were dying with a disease for which there was no treatment. And then medicine seemed much less important than the human being and their... Their particular journey. And so that led me to more and more writing and my ambition with my first work of fiction. The book 'Cutting for Stone' was really to write a book similar to of 'Human Bondage', not in terms of the story, but in terms of some young age or school age. I was a schoolboy when I read that. Someone picking that book up and saying, "You know. I don't care how difficult medicine will be or whether it's not going to pay or whether it's full of stress. But I can't imagine a more romantic and adventurous life than being a physician." So that was my goal because. You know, it's still a... I think of it as an incredibly romantic, adventurous pursuit, you know, the great privilege of walking into that hospital. And sometimes you have to remind yourself of that, you know, the great privilege of running into Tyler in the corridor and chatting with him about a mutual patient and expressing my angst or his angst, you know. Often times I'm close to tears talking to him because of the patients we're taking care of. And wow, you know, what an extraordinary adventure that is. I don't think I traded for anything. I mean, that's not the goal every single time I sit down to write. But I think it's coming from that same impulse to to share the richness of what I'm living.

Tyler Johnson: [00:35:45] One thing that I think that some people that I have talked to... One sentiment that they have expressed is we might talk about things similar to the things that we've talked about today. And they might say, well, yeah, like I understand on some we've used the word philosophy a lot, some philosophical level that this approach to medicine is important or this way of thinking about things. But this gets a little bit, to Henry's point, in the day to day busyness of being a doctor, whether that's a primary care doctor who's responsible for 18 different aspects of each patient's care and has 18 different patients to see in a day, or whether that's a doctor working in the hospital who's running back and forth, sometimes from crisis to crisis. It just can feel difficult when the rubber meets the road to get all of this big philosophical stuff that's kind of up here in the air, somewhere down into the daily practice of actually being a doctor. And so what advice would you give to someone who's maybe starting on their medical career and feels like maybe they have a sense for this now? They've read or heard things that you've said or written, and they want to maintain touch with that. But they're just worried that in the busyness of everyday doctor life that they'll lose touch with it. What can they do on a daily or hourly basis to try to keep touch with these deeper meanings?

Dr. Abraham Verghese: [00:37:08] Again, I want to make sure it's clear. I'm not acknowledging that people do detailed exams on every patient, every time you see them. You know, I think the trick is you and I know which patient it is. We need to pull out all stops and let everything else slide by that day and back up because they really need more than what we had embarked on. I would like to convey to people in training especially, you know, you make a great leap in your cognitive knowledge and your... Your base of knowledge as you as you go through your training. But if your ability to examine a patient and quickly discern something is at the same level it was when you entered, then in a way, we failed you. So I would like to leave people with the belief that if they're called because a patient... Something has happened... that their first instinct should be to go see the patient rather than order a CAT scan because the nurse says they're having belly pain. You may order a CAT scan anyway, but you might find that there's something else going on. And I would like them to sort of have the confidence in their abilities and if they don't have it, keep continuing to develop it to where they would want that to be the first step. There are times when remotely you order this and you order that, and I quite understand, but too often, not only waste more of your time, then... Then you realize.

Dr. Abraham Verghese: [00:38:34] So the thing that makes being attending interesting for me is it just the things I will learn from my incredible house staff and my cognitive knowledge base expanding? To me, it's much more the richness of what I might see on the patient and what I will learn in that interaction and the connection I'll make, however brief it is or however meaningful or meaningless it is. And so... But a lot of that comes from confidence that the therapeutic instrument is you. I think people don't often realize that, you know, you're walking in there with a certain level of confidence in your skills. You're putting your hands on them. Not to put your hands on them, but in a knowledgeable knowing way, makes the great difference, not just in your ability to assess them, but in their in their level of connection with you. So many disorders out there, you know, are not cut and dry. There's a tremendous placebo effect that has everything to do with the patients buying in with this relationship. And if you if you neglect the relationship, it only makes things more tricky or difficult,

Dr. Abraham Verghese: [00:39:49] I think. If I can give you one memorable example I was attending, it might have been it's a long time ago now, but it stuck with me. Someone was transferred from the nursing home. And, you know, that's another subject in itself. Why, who? Who transferred them? What was really wrong? And there's no one around to interrogate. And by the next morning, the patient is fine and ready to go back. But I was told that the patient's daughter is a lawyer and agitated, that her mother has just been transferred and already we're ready to send the person back. And I haven't seen the patient yet. I'm hearing all the second hand. So I walk in there prepared for a push back and I just introduced myself and I said, I haven't actually seen your mother yet, so do you mind if I take a look? And I actually did a quick exam. I did a neurological exam because the patient had a stroke. I pulled out my reflex hammer, which actually is kind of a magic one because nobody else carries it. And I did a quick neuro exam, a quick check of her, and I turned to the doctor and said, you know, honestly, I don't really know what happened last night, but I can tell you that she looks fairly stable now. And I think that it would be best to get her out back there where she's comfortable rather than a hospital with all its inherent risk. And she said, okay, you know, and I felt like, you know, that was proof to me, anyway, that that exam matter is your assessment as a human being rather than reporting numbers, you know, all your potassium is fine. That's just x rays. Fine. We did a CAT scan. She's fine, but doesn't buy it quite enough. So I'd like to just tell your listeners to have faith in who they are, how they present themselves. You know, as William Carlos Williams once said, you know, you're not dealing with a disease. You're dealing with one guy, one gal in distress, you know, dealing with it in their special way. And your job is to acknowledge that, recognize that, and help them on that journey.

Tyler Johnson: [00:41:53] Dr. Verghese, we thank you so much for being with us. And I heard through the grapevine that maybe in the not too distant future there could be another book coming. Is that true?

Dr. Abraham Verghese: [00:42:03] Yeah, it's true. I just submitted my book for copyediting and it's coming out in May of 2023. So we're already talking about fonts and this and that, which is exciting. It's been a long journey, as you know, with some hitches along the way. So I'm excited. But, you know, I'm never in a great hurry with my writing because I have a great day job. And so the writing is just gravy, you know, it happens.

Tyler Johnson: [00:42:25] Well, we'll... We'll take that as a date to look forward to. And again, we thank you so much for your time and we'll talk to you again soon.

Dr. Abraham Verghese: [00:42:32] Great to be with both of you. And thanks for asking me. I appreciate it.

Henry Bair: [00:42:37] Thank you for joining our conversation on this week's episode of The Doctor's Art. You can find program notes and transcripts of all episodes at www.theDoctorsArt.com If you enjoyed the episode, please subscribe, rate and review our show available for free on Spotify, Apple Podcasts or wherever you get your podcasts.

Tyler Johnson: [00:42:56] We also encourage you to share the podcast with any friends or colleagues who you think might enjoy the program. And if you know of a doctor patient or anyone working in health care who would love to explore meaning in medicine with us on the show. Feel free to leave a suggestion in the comments.

Henry Bair: [00:43:10] I'm Henry Bair.

Tyler Johnson: [00:43:11] And I'm Tyler Johnson. We hope you can join us next time. Until then, be well.

You Might Also Like

LINKS

Read more about Dr. Verghese at AbrahamVerghese.org.

Follow Dr. Verghese on Twitter @cuttingforstone.